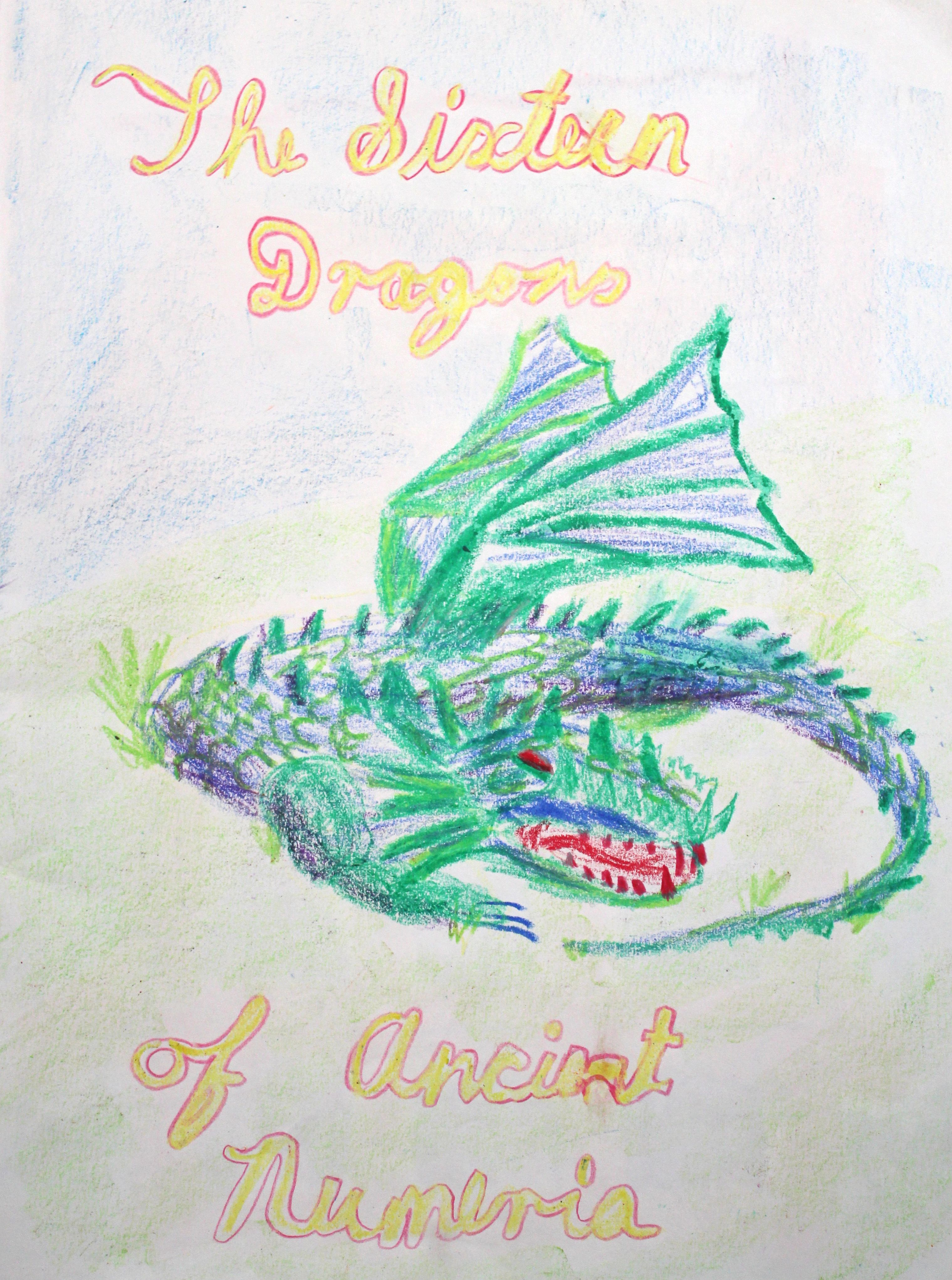

A vivid green dragon extends its wings and breathes a volcanic gust of flame before settling quietly on the school book page. Is this a scene from Harry Potter? Maybe the opening frames of a new Disney blockbuster? Perhaps a Year 3 arithmetic textbook as envisioned and hand-drawn by the student herself?

If you guessed the last, you may already be familiar with the central pillars of the Steiner teaching method: creativity, imagination, experiential learning and a holistic approach to education that aligns with the developmental stages of childhood.

“We have a picture of child development that lies behind what we do. At each stage of the school journey there are specific ways that we work with the child to match what we have observed over time to be the ways children learn,” says Glenaeon Rudolf Steiner School principal Andrew Hill. “It produces happy, adjusted children because we’re meeting the child’s specific needs at each stage.”

This developmental emphasis is seen most distinctly in the early years of Steiner schooling when children are encouraged to learn through active play and imitation. Singing, dancing, movement and story time are complemented with practical skills like knitting, cooking, sewing and gardening. Learning is almost entirely a physical activity at this stage with formal literacy and numeracy lessons delayed until students are intellectually ready.

“They go through a change around the age of seven when they start to learn through more abstract thought, rather than concrete bodily experience; they start to learn through imagination and images. That’s why they’re so receptive to stories and the arts,” Mr Hill says.

This is followed by the third stage of learning when children acquire conceptual and analytical skills, Mr Hill says. “Gradually, the rational intellect unfolds, around 10-12, that’s when they start to make connections between things. They can see cause and effect and that becomes the way they learn as adults.”

“The broad benefit of a Steiner education is learning in ways that are more natural. I like to think of it as like organic farming. It’s organic education. We fit in with the child’s natural rate of growth,” Mr Hill says.

In practice, this means the emphasis in the first years of schooling is on developing the foundations of learning through creative pursuits. One of the first activities is drawing, which leads into writing, which leads into reading.

As Mr Hill explains: “Children create their own first readers, handwritten and illustrated in Year 1. Teachers tell stories to build imagination and stimulate a creative understanding, which, in turn, is the foundation of comprehension in literacy. The research shows that they quickly catch up to, and typically surpass, students in other systems. Late is more: evidence from an international, peer-reviewed study shows that as a group, students from Steiner schools start reading later but then exceed the reading fluency of mainstream students who started earlier.”

Mr Hill says his personal experience bears out these findings, even in the occasional case where students appear to be worryingly slow to catch on.

“It’s a case of the Hare and the Tortoise: slow and steady wins the race. Like Finland, we don’t teach formal reading until around age seven and it takes another year or so before it kicks in. We had one girl who still wasn’t getting it when she was eight. She had all the elements in place, we’d measured everything. The parents were anxious but they trusted us and, eventually, just after age nine, she started to read. She went through a very gentle, natural process and by the time she was 10, she was reading ravenously. She’s now a pediatrician,” Mr Hill says.

“Not all children who are slow to read fall into this category of course, and students with learning issues are assessed and supported with a range of strategies.”

Steiner education, also known as Waldorf education, is named for its founder, Austrian polymath Rudolf Steiner, who also developed the theory of biodynamic agriculture.

He established the Steiner movement in 1919 with the opening of a school at the Waldorf-Astoria factory in Stuttgart, Germany. The school was an immediate success and Steiner schools quickly proliferated throughout Britain and Europe.

In 1957, the movement came to Australia with the founding of Glenaeon Rudolf Steiner School. There are now more than 40 Steiner schools throughout Australia as well as Steiner streams in some public schools in Victoria and South Australia.

The Steiner method has some defining characteristics rarely seen in mainstream schools.

In the primary school years, students have one teacher throughout years 1-6. This approach is based on the Nordic model, Mr Hill says, and the aim is to create a secure, tightly-knit class community in which students are very well known to their teachers and to each other.

Immersive learning is another hallmark of Steiner education. School days begin with a two-hour “main lesson”, in which a broad topic is taught from a multi-disciplinary perspective for a period of three weeks. Teachers present the material with drama and artistry to capture students’ imaginations and inspire them to produce their own beautifully illustrated textbooks.

“Even with Maths they try to build the lesson around an imaginative story that is going to excite their students and keep their interest throughout. They’re learning all the standard Maths but it’s filled out with this wonderful rich imagination,” Mr Hill says.

Committed to developing global citizens, Glenaeon pioneered languages in primary school in Sydney: all students learn two foreign languages up to Year 6 and then choose one to continue learning in Years 7-10, after which it becomes an elective.

In primary school, students develop their human faculties first: drawing, handwriting, playing musical instruments, and importantly learning to use tools to make useful and beautiful artifacts in textiles, wool, wood and metal. The school calls its use of technology the Artisan program which builds practical and entrepreneurial skills. Digital technology on the other hand is eschewed until high school when ICT is integrated into learning. Natural materials are used as much as possible throughout the school.

Once students reach high school level, Glenaeon is not particularly different to a mainstream school because teenagers learn similarly to adults, Mr Hill says. However, the five foundational programs of Steiner education: Academic, Aesthetic, Artisan, Active Wilderness and Altruistic are intrinsic to all the years.

The effect of these programs is seen in Glenaeon’s excellent HSC results, its emphasis on the creative and performing arts and craftsmanship, its extensive outdoor education program and its deep emphasis on mutual respect and personal responsibility.

The school’s low incidence of bullying is consistent with research showing that bullying is a rare occurrence in Steiner schools generally. Mr Hill attributes this happy outcome to Glenaeon’s discouragement of competitiveness between students.

“It’s a very rigorous education but it’s done with this more positive relational quality of working with students and a class as a community. Students work and do well, not to beat other children, but to be their best and that has an effect on the mood in the classroom,” Mr Hill says.

With its focus on creativity, wellbeing and self-reliance Steiner education is a child-centric pedagogy whose time has come, Mr Hill says. “Many schools talk about positive education these days but we’ve always been positive. Positivity is implicit in the method we use.”

“We pioneered a holistic approach to education that genuinely fosters the overall wellbeing of students on all fronts; recognising that a successful life is made up of a balance between intellectual growth, emotional maturity and a practical ability to do things in the world rather than a simplistic academic measure of competence. The ATAR is important as a measure of intellectual excellence, but the world is looking for more than just that as a predictor of personal and professional success.

“I’ve been teaching in different schools for 30 years. The greatest reward is seeing students grow and develop and, after all they work they’ve put into it, become the person they were destined to be.”

References:

Children learning to read later catch up to children reading earlier — Sebastian Suggate, Elizabeth Schaughency, Elaine Reese, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 2013

https://web.uvic.ca/~gtreloar/Articles/Language%20Arts/Children%20learning%20to%20read%20later%20catch%20up%20to%20children%20reading%20earlier.pdf

Addressing bullying in schools: theory and practice — Ken Rigby, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2003

https://aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi259